About Persian Carpets

Masterpieces of Persian Art

By Arthur Upham Pope

Carpets are in the West the best known and loved of all the Persian arts. They have been collected with passion ever since the days of Henry VIII when the Duke of Buckingham held up a treaty until he could get the Persian carpets he coveted for Hampton Court. Rubens, Van Dyke, and other European painters owned them, understood them, and frequently used them in their paintings - a fortunate circumstance that greatly helps dating problems. It is in fact the painters themselves who are largely responsible for the high artistic repute of these fabrics - John Singer Sargent once wrote of a Herat carpet now in the Gardener Museum of Boston, " I have seen today a carpet more beautiful than any picture ever painted;" and in speaking of the Milan Hunting carpet, Sir Charles Holmes, painter and critic, unknowingly used almost the precise words.

Because of the limitations generally accepted in the West concerning the nature of art, which obscures some of its purpose and values, it is difficult for us to believe that despite the testimony of artists and critics, despite our fondness for the later examples, colored yarns could be so woven and composed as to comprise a work of art of the very highest quality. But the proof is there in the carpets themselves and convincing it is to any who are fortunate enough to see the great examples with an open mind, a responsive eye, and the necessary leisure.

There were famous carpets of vast size in Sasanian times and in the possession of Haroun al Rashid and his successors. They were made of silk, enriched with gold thread, and thickly studded with jewels. The so-called spring Carpet of Khosrau, which was in reality a whole section of the royal treasury on display could not have cost less than two hundred million dollars.

Rugs had been important adjuncts to the royal palace since early Assyrian times. Cyrus the Great owned costly Babylonian carpets and they continued apparently throughout the centuries to command the services of the greatest designers and technicians available.

They reached their apogee in Persia in the sixteenth century. Under royal patronage, that spared no expense and demanded only the most perfect results, aided by the full development of the dyer's art, and having at hand for the cartoons the most gifted illuminators who embodied in their art the genius, skill, and impeccable taste, it is not surprising that the results achieved defy comparison.

A really great carpet does not reveal its quality at once no matter how impressive at first view. In cost, in time, in effort, and in talent they vie with the most ambitious productions known to art, and like them demand time and effort for their full understanding.

Into these majestic fabrics went the full resources of many centuries of the richest decorative tradition known. The finest carpets are as complex as symphonies, as rich in color as any painting, and as costly as palaces. They make real demands on those that would understand them. A systematic and detailed analysis which may subsequently be resynthesized into a moment of intense aesthetic emotion is the indispensable preliminary to the realization of their characteristic merits. Black and white illustrations that may be less than one hundredth of the original in an art where magnitude itself is vital can be little more than a record of the pattern. But even these shadows if carefully studied can be very rewarding.

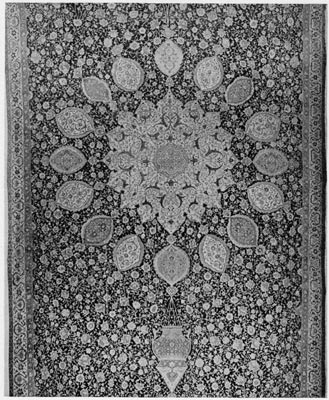

The most perfectly preserved carpet of the 16th century, which once belonged to the Duke of Anhalt (Pl. 140), is typical of the first half of the century. The field under proper illumination is bright golden yellow, the border and central medallion deep scarlet. The patterns are in cerulean blue, black, and white. The scale is majestic, the colors brilliant and harmonious, the patterns animated and graceful - the whole has an air of jubilation and splendor.

For although these are precisely formal compositions, with each element in exquisite balance, and although there is no pictorial element to call to aid adventitious sentiment, none the less pure and abstract form are deployed with such mastery that a powerful and valid emotion is expressed with commanding force. This is abstract art at its finest and most real.

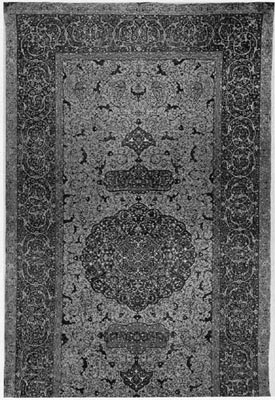

The section of the mate to the famous Ardabil carpet (Pl. 143). for these great carpets were originally made in pairs, is deeper and quieter than its contemporary and more appropriate to the holy place it was woven to adorn. It was ordered for the sacred shrine dedicated to the founder of the Safavid dynasty, and Maksoud of Kashan, the weaver who signed it in the year 1537, was probably the greatest master of his day rivaled only by Ghiyath ad-Din Jami who boasted of his prowess in an inscription in the great Hunting carpet of Milan which he finished in 1522-3. In the Ardabil carpet a golden sun-burst medallion dominates a field of glowing midnight blue which is densely covered with blossoms and tendrils, exquisitely drawn and ingeniously distributed to give the effect of an infinite wealth of abundant life. It is again the age-old scheme of fertility - an apostrophe to the sun and its power to evoke a paradise of bloom. For this is the old Iranian notion of Paradise, the flowering garden - the reward and rescue from the hardships of pilgrimage, surcease from pain and effort - tranquil and healing perfection. The plan is true to the oldest conceptions, for in prehistoric time the sun was associated with a mysterious atmosphere pool from which the sun drew the beneficent rain, the other essential of fertility and here at the heart of the "sun" medallion is a little pool of gray-green water with lotus blossoms floating on it. The pendant mosque lamp, a reminder of the sacred destiny of this carpet, is substituted for the conventional bar and pendant, but it is a little too pictorial and too detached from the texture and movement of the whole design to be wholly successful and the experiment was not repeated in Persian carpets.

Probably both of these great carpets were woven in the court ateliers at Tabriz. The wool is the firm sparkling white wool that comes from Ahar a little to the northwest and the method of knotting that gives a brisk erect pile is characteristic of later Tabriz weaving.

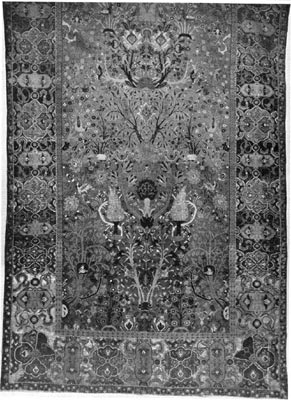

The garden in its infinite manifestations is the theme of most Persian carpets. Sometimes they are abstract, like the Ardabil and Anhalt and the so-called Isfahans; occasionally they are quite pictorial (Pl. 142), recalling the miniatures and the marginal page illuminations. This carpet, woven about the turn of the century as is indicated by the form of the cloud bands, shows a charming bird-haunted garden - all manner of trees and shrubs and blossoming plants - silhouetted in successive registers against a fround of fluctuating crimson. It is in a more jubilant mood than the solemn Ardabil carpet, intense though that is; and, although simplified and in silhouette, it has caught the essentials and conveys the joy in gardens which meant so much to the Persians.

Persian carpets, for all the variety and beauty of their color and color combinations, when compared to some of the Turkish and Indian carpets may seem a little wanting. The Persian tradition knew the values of understatement in such matters, and seems to have felt the danger of submerging poetic implication by powerful over-dominant tones that might obscure the more subtle relations - quieter passages that modestly wait to be explored. These designers always had in view the secondary and lasting effects; they assumed the repeated and leisurely examination such as Persians gave to their verse, their philosophy and all their art. They suspected the sudden and overwhelming effect that gave too much too quickly - musically they would have preferred strings to brasses.

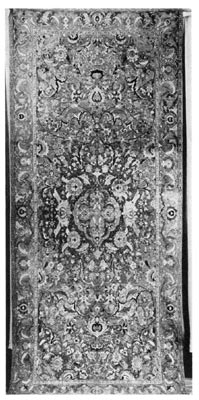

It was only in the 16th century that prayer rugs of high quality were designed and woven in Persia (Pl. E). The details of these few fine pieces repay the most careful study: for example, in the lower border of the Fletcher rug, there are two systems of spiral tendrils; the primary a little more emphatic, terminating in lovely little arabesque blossoms, the secondary suppressed like an obligato, each moving in different circuits and different rhythms, with tangential collisions, parallel movements that capriciously break away, only to be resolved and united in beautifully drawn palmettes or graceful corners, one of the most difficult of all weaving problems.

But as this is a prayer carpet, its holy office comes first. The cartouches of the border contain texts from the Koran; but more is necessary for fullest communion. Texts are distributed in both the inner and the outer borders; the little square panels contain Koranic verses in conventionalized Kufic; the prayer arch and the central panel, where one lays the head in obeisance, and the clouds of heaven above the dome-like panel are filled with the message of the Holy Word. Much scripture is compressed within a small area. The rug itself thus becomes a prayer, reinforcing and elevating the spirit of the worshipper. But the ecclesiastical intent, particularly in the effort to find too literal sermons in clouds, was not wholly successful. Calligraphy, noblest of ornament, needs to be confined within a formal space.

Yet in their more exultant moods they could manage sheer color of a depth and intensity that vied with anything, as the northwest Persia medallion carpet (frontispiece) proves. (Unfortunately the glowing quality of the original is beyond the range of our photo-engraving craft.) The ground of the central medallion is midnight blue, there are passages in the corners and the border of clear and intense emerald green such as is not be found in any other Persian rug. Areas of an intense violet blue in the corner and medallion margins and scattered blossoms in saffron are equally unusual athough they later reappear in a few rare pieces from eastern Anatolia. The saffron so well and discreetly distributed is an ideal tone for softening the otherwise too hot red. The white of the palmettes and the inner border and scattered details add a welcome note of freshness that quiets the intensity of the dominant red.

All this exuberance of color escapes the vulgar and obvious, first by the purity, mellowness, and harmonious balance of all the tones - an effect possible only if wool and dyes are of the very finest and the taste of the designer impeccable. It is frankly a red rug and the red is allowed a complete dominance that gives a primal unity to the whole. The furious energy of this exciting color is further constrained and absorbed by the strength of the basic design; a powerful and complex central medallion, strong corner segments, and a wide border with large palmettes separate huge conventionalized alternately colored and directed palmettes.

A timid, theoretical, and uninformed taste some years ago declared red as "no longer acceptable to people of refinement". These Canute-like decrees that defy basic and permanent human preferences are as common as they are futile in all ages of slackening vigor, emotional insecurity, and compensatory snobbism. Our aesthetic life is but temporarily impoverished thereby until some splendid and vital creation full of a zest for life, like this carpet, recalls us to common sense and to the full enjoyment of ofur artistic sensibilities.

Silk is a dubious and difficult material for carpets. It lacks the substance and seriousness of wool, its sheen is apt to appear a little flashy - tending to compromise the dignity of a design or any claim to permanent and ideal values beyond the first effect. But the sixteenth century velvet weavers had produced a whole series of figured velvets of such pure and deep intensity of color, such perfection of polychromatic harmonies, that their appeal was irrestible and constituted a sharp challenge to the designers. The rivalry was especially acute in Kashan, then the capital of the textile art, rivalled though it was by Yazd and later by Isfahan. The velvet makers could surpass the rug weavers in sheer luxury of color - the rug weavers had the advantage of complete freedom of design unhampered by problems of loom width or other simplifications necessitated by the mechanics of the craft. So in the second half of the sixteenth century there apppeared out of the Kashan shops a series of small rugs, and three huge ones - the Hunting Carpet of Vienna, the Prince Branicki Carpet of Warsaw, and the Hunting Carpet of the King of Sweden. They were a match for the depth and brillliance of the velvet, nor were they lacking in grandeur or nobility, thanks to the services of some great designers. The contest was so equal because both used the same silk, spun in the same shops, and dyed in the same pots. They apparently also had recourse to the same cartoon makers.

These are pieces that must be seen, and seen in proper light. The best color plate reproduction is only a reminder of their quality, like a piece of shorthand that is hard to read.

The designs are sometimes too pictorial and tend to become velvet pictures - but the Morgan piece (which passed through the Widener Collection to the National Gallery [Pl. F] has a basic simplicity that comes from the traditional quatrefoil medallion and a general largeness of basic pattern that gives it the necessary aristocratic reserve.

A full analysis of the subtleties of color and pattern in these carpets is a lengthy affair indeed, and even so it has really to be done by the serious observer himself.

These Kashan silk rugs, which in themselves seemed to have reached the acme of luxury, were followed by an even more gorgeous and opulent creation, probably also, at first at least, a product of the Kashan looms - the so-called Polonaise group. They owe nothing of their origin to Poland, although the Poles were the first to appreciate, collect, and preserve them. They are in rather startling high key. Some are deep crimson and ruby like the prior silk carpets, but most exploit a new range of colors that were made possible by the remarkable development of the dyer's art at this time. There are all the tones of yellow, and especially lovely salmon and orange tones set off by a fresh light green that is a new note in Persian fabrics. To add to this splendor of color, they are richly interwoven with silver and gold thread. The gold thread is really silver gilt - a very thin flat wire wrapped around a silk thread and then brocaded into the warp and weft. A great many of these carpets have suffered grievously at the hands of time, the pile destroyed, the colors faded, the silver blackened, and the gold picked out. But when in anything like the original condition, they achieve a tour de force which in terms of its own ideal and intents has never been equalled. The European travelers of the time as well as the collectors of the day have been completely fascinated by them.